Bird-Friendly Agriculture: Finding the Right Balance to Benefit Birds and Farmers (and Everyone Else)

January 19, 2022 - Diane Huhn

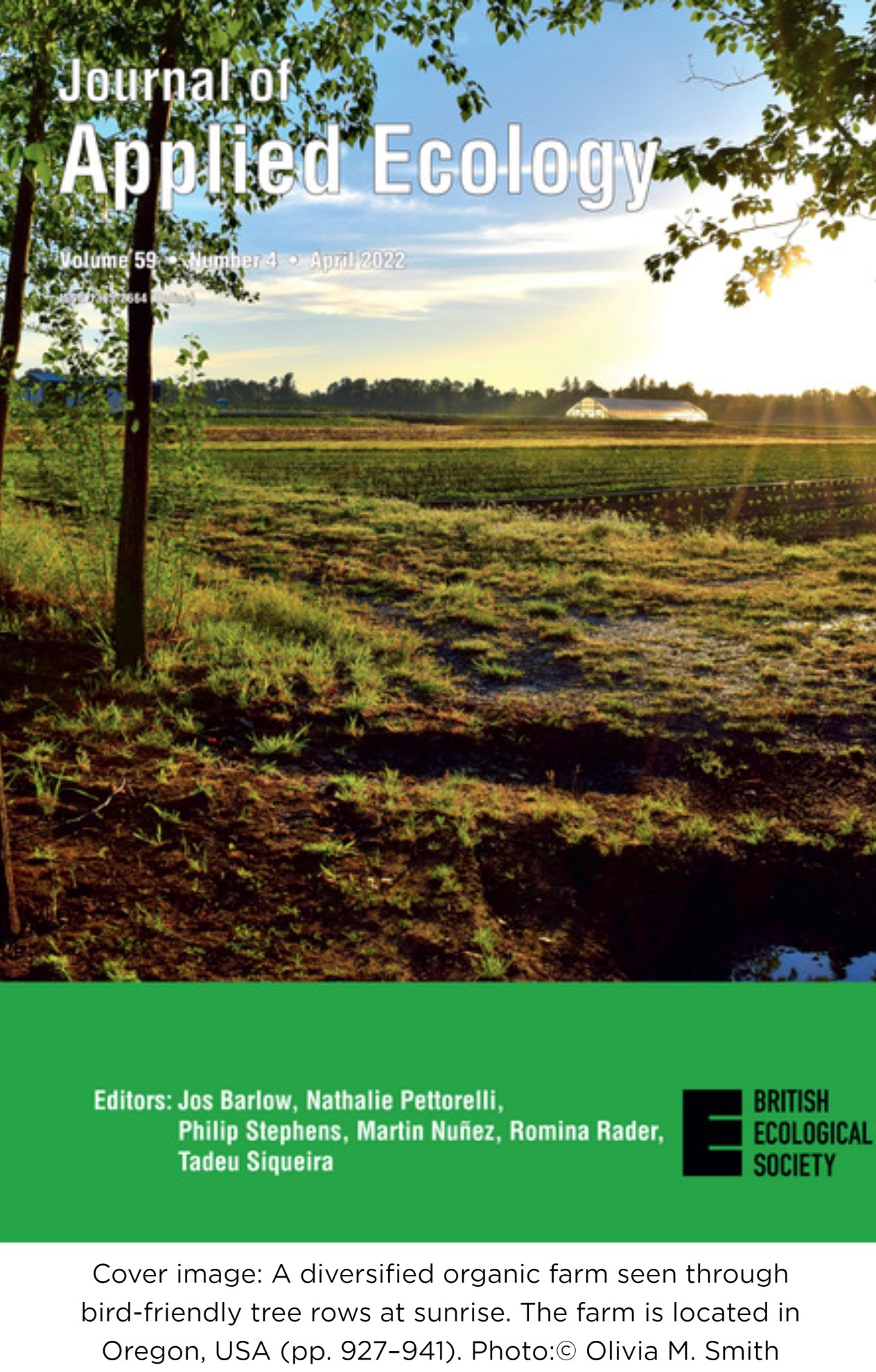

Farmer manually removing weeds from a broccoli field on a farm embedded in a forested landscape near Portland, Oregon. Credit: Olivia Smith

Birds and farmers don’t always get along. But just as birds can sometimes be a farmer’s worst enemy, so too can the farming industry negatively impact avian populations, often through habitat loss due to agricultural intensification. But when we can figure out how to get birds and farmers working together, it’s clear that we all benefit. For that reason, researchers at Michigan State University (MSU) are working to determine how best to act as matchmakers between birds and farmers. The goal is to create long-term, mutually beneficial relationships between the two to increase sustainability. As outlined in a new article in the Journal of Applied Ecology, Olivia Smith and her co-authors report that farmers can use landscape and farm diversification practices to more effectively harness ecosystem services provided by birds while deterring harms from birds.

Birds and farmers don’t always get along. But just as birds can sometimes be a farmer’s worst enemy, so too can the farming industry negatively impact avian populations, often through habitat loss due to agricultural intensification. But when we can figure out how to get birds and farmers working together, it’s clear that we all benefit. For that reason, researchers at Michigan State University (MSU) are working to determine how best to act as matchmakers between birds and farmers. The goal is to create long-term, mutually beneficial relationships between the two to increase sustainability. As outlined in a new article in the Journal of Applied Ecology, Olivia Smith and her co-authors report that farmers can use landscape and farm diversification practices to more effectively harness ecosystem services provided by birds while deterring harms from birds.

“Management of birds within agroecosystems can be a highly contentious issue, impacting a wide range of stakeholders beyond individual farmers. For example, we sometimes see pressure to exclude birds and other wildlife from farms for fear that they may carry foodborne pathogens,” said Smith, a Research Associate at the Center for Global Change and Earth Observations and an MSU Presidential Postdoctoral Fellow with the Ecology, Evolution and Behavior Program. However, others advocate for conserving birds on farms, both because birds are in rapid decline and because some farmers want to leverage the pest control services they provide. However, many farmers operate within very tight margins and generally do not have the time or money to experiment with the effectiveness of different habitat types.

Research such as that conducted by Smith and her team can improve farmer decision-making and better harness the positive services birds can provide, and lessen the negative ones. “This work can be a bit of a balancing act at times, but our central goal is to identify aspects of agroecosystems that best support birds for multi-functional outcomes. We’re really looking for those agricultural land-use practices that provide us with a win-win situation.”

Research such as that conducted by Smith and her team can improve farmer decision-making and better harness the positive services birds can provide, and lessen the negative ones. “This work can be a bit of a balancing act at times, but our central goal is to identify aspects of agroecosystems that best support birds for multi-functional outcomes. We’re really looking for those agricultural land-use practices that provide us with a win-win situation.”

Such research is critical and becoming more so as time progresses. Since the 1970s, we’ve witnessed a decline of nearly 30% of the bird population in North America due primarily to habitat loss, deforestation, and climate change. By compromising the important ecosystem services birds provide, this rapid loss is likely to have severe consequences for the future functioning of coupled human-natural systems such as those found in agriculture.

To determine how farmers can maximize the ecosystem services provided by birds, Smith and her team surveyed bird communities on a total of 27 farms in Oregon and Washington states over a four-year period from 2016-2019. The farms were highly diversified, growing a wide range of crops such as cereals, vegetables and melons, fruits and nuts, oilseed crops, roots, spice crops, beverage crops, medicinal crops, commercial flowers, and grasses and fodder crops, among others. Most of the farms used organic practices, some integrated livestock into farming operations, and landscape types ranged from intensified agriculture to primarily seminatural habitats.

“By classifying the ecosystem services and disservices of these bird communities, we found evidence that suggests that farmers can promote higher abundances of beneficial birds through whole-scale farm diversification,” said Smith. “This is really exciting because we’re not only able to help farmers determine best practices that can increase their yields, but these practices can also help maintain, restore, and create habitat types that promote overall biodiversity and benefit many declining bird species.” These findings also suggest the need for greater public policy and farmer incentives for landscape-scale planning to promote seminatural land cover at landscape scales.

To learn more about this research, see “Complex landscapes stabilize farm bird communities and their expected ecosystem services” in the Journal of Applied Ecology.